The Dark Energy Survey (DES) collaboration is releasing results that, for the first time, combine all six years of data from weak lensing and galaxy clustering probes. In the paper, which represents a summary of 18 supporting papers, they also present their first results found by combining all four probes — baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), type-Ia supernovae, galaxy clusters, and weak gravitational lensing — as proposed at the inception of DES 25 years ago.

“The methodologies that our team developed form the bedrock of next-generation surveys.”

Alexandra Amon, co-lead of the DES weak lensing working group

“DES really showcases how we can use multiple different measurements from the same sky images. I think that’s very powerful,” said Martin Crocce, research associate professor at the Institute for Space Science in Barcelona and co-coordinator of the analysis. “This is the only time it has been done in the current generation of dark energy experiments.”

The analysis yielded new, tighter constraints that narrow down the possible models for how the universe behaves. These constraints are more than twice as strong as those from past DES analyses, while remaining consistent with previous DES results.

“There’s something very exciting about pulling the different cosmological probes together,” said Chihway Chang, associate professor at the University of Chicago and co-chair of the DES science committee. “It’s quite unique to DES that we have the expertise to do this.”

How to measure dark energy

About a century ago, astronomers noticed that distant galaxies appeared to be moving away from us. In fact, the farther away a galaxy is, the faster it recedes. This provided the first key evidence that the universe is expanding. But since the universe is permeated by gravity, a force that pulls matter together, astronomers expected the expansion would slow down over time.

Then, in 1998, two independent teams of cosmologists used distant supernovae to discover that the universe’s expansion is accelerating rather than slowing. To explain these observations, they proposed a new kind of energy that is responsible for driving the universe’s accelerated expansion: dark energy. Astrophysicists now believe dark energy makes up about 70% of the mass-energy density of the universe. Yet, we still know very little about it.

In the following years, scientists began devising experiments to study dark energy, including the Dark Energy Survey. Today, DES is an international collaboration of over 400 astrophysicists and scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries. Led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, the DES collaboration also includes scientists from U.S. universities, NSF NOIRLab and DOE national laboratories Argonne, Lawrence Berkeley and SLAC.

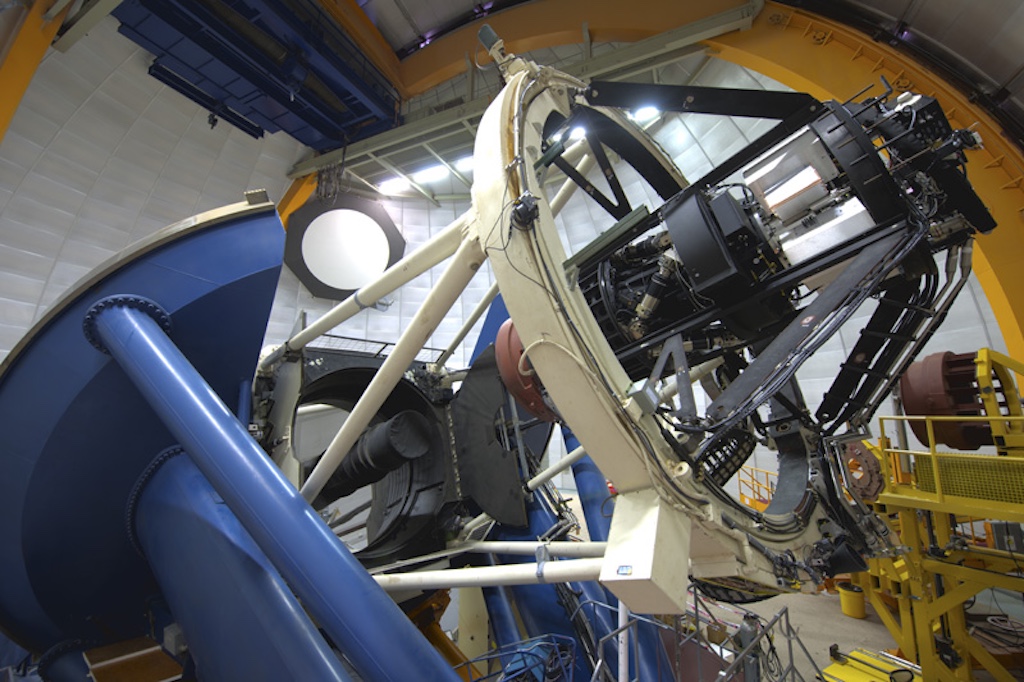

To study dark energy, the DES collaboration carried out a deep, wide-area survey of the sky from 2013 to 2019. Fermilab built an extremely sensitive 570-megapixel digital camera, DECam, and installed it on the U.S. National Science Foundation Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope at NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a Program of NSF NOIRLab, in the Chilean Andes. For 758 nights over six years, the DES collaboration recorded information from 669 million galaxies that are billions of light-years from Earth, covering an eighth of the sky.

For the latest results, DES scientists greatly advanced methods using weak lensing to robustly reconstruct the distribution of matter in the universe. They did this by measuring the probability of two galaxies being a certain distance apart and the probability that they are also distorted similarly by weak lensing. By reconstructing the matter distribution over 6 billion years of cosmic history, these measurements of weak lensing and galaxy distribution tell scientists how much dark energy and dark matter there is at each moment.

“One of the most exciting parts of the final DES analysis is the advancement in calibrating the data,” said Alexandra Amon, co-lead of the DES weak lensing working group and assistant professor of astrophysics at Princeton University. “The methodologies that our team developed form the bedrock of next-generation surveys.”

In this analysis, DES tested their data against two models of the universe: the currently accepted standard model of cosmology — Lambda cold dark matter (ΛCDM) — in which the dark energy density is constant, and an extended model in which the dark energy density evolves over time — wCDM.

DES found that their data mostly aligned with the standard model of cosmology. Their data also fit the evolving dark energy model, but no better than they fit the standard model.

However, one parameter is still off. Based on measurements of the early universe, both the standard and evolving dark energy models predict how matter in the universe clusters at later times — times probed by surveys like DES. In previous analyses, galaxy clustering was found to be different from what was predicted. When DES added the most recent data, that gap widened, but not yet to the point of certainty that the standard model of cosmology is incorrect. The difference persisted even when DES combined their data with those of other experiments.

“What we are finding is that both the standard model and evolving dark energy model fit the early and late universe observations well, but not perfectly,” said Judit Prat, co-lead of the DES weak lensing working group and the Nordita Fellow at the Stockholm University and the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden.

Paving the way

Next, DES will combine this work with the most recent constraints from other dark energy experiments to investigate alternative gravity and dark energy models. This analysis is also important because it paves the way for the new NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, to do similar work with its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

“The measurements will get tighter and tighter in only a few years,” said Anna Porredon, co-lead of the DES Large Scale Structure working group and senior fellow at the Center for Energy, Environmental and Technological Research (CIEMAT) in Madrid. “We have added a significant step in precision, but all these measurements are going to improve much more with new observations from Rubin Observatory and other telescopes. It’s exciting that we will probably have some of the answers about dark energy in the next 10 years.”

More information on the DES collaboration and the funding for this project can be found on the DES website.

The Dark Energy Survey is jointly supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.