BATAVIA, Illinois-Scientists of the MINOS experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator laboratory today (June 14) announced the world’s most precise measurement to date of the parameters that govern antineutrino oscillations, the back-and-forth transformations of antineutrinos from one type to another. This result provides information about the difference in mass between different antineutrino types. The measurement showed an unexpected variance in the values for neutrinos and antineutrinos. This mass difference parameter, called Δm2 (“delta m squared”), is smaller by approximately 40 percent for neutrinos than for antineutrinos.

However, there is a still a five percent probability that Δm2 is actually the same for neutrinos and antineutrinos. With such a level of uncertainty, MINOS physicists need more data and analysis to know for certain if the variance is real.

Neutrinos and antineutrinos behave differently in many respects, but the MINOS results, presented today at the Neutrino 2010 conference in Athens, Greece, and in a seminar at Fermilab, are the first observation of a potential fundamental difference that established physical theory could not explain.

“Everything we know up to now about neutrinos would tell you that our measured mass difference parameters should be very similar for neutrinos and antineutrinos,” said MINOS co-spokesperson Rob Plunkett. “If this result holds up, it would signal a fundamentally new property of the neutrino-antineutrino system. The implications of this difference for the physics of the universe would be profound.”

The NUMI beam is capable of producing intense beams of either antineutrinos or neutrinos. This capability allowed the experimenters to measure the unexpected mass difference parameters. The measurement also relies on the unique characteristics of the MINOS detector, particularly its magnetic field, which allows the detector to separate the positively and negatively charged muons resulting from interactions of antineutrinos and neutrinos, respectively. MINOS scientists have also updated their measurement of the standard oscillation parameters for muon neutrinos, providing an extremely precise value of Δm2.

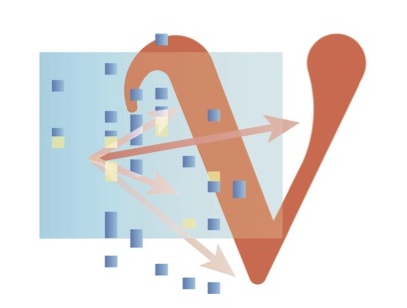

Muon antineutrinos are produced in a beam originating in Fermilab’s Main Injector. The antineutrinos’ extremely rare interactions with matter allow most of them to pass through the Earth unperturbed. A small number, however, interact in the MINOS detector, located 735 km away from Fermilab in Soudan, Minnesota. During their journey, which lasts 2.5 milliseconds, the particles oscillate in a process governed by a difference between their mass states.

“We do know that a difference of this size in the behavior of neutrinos and antineutrinos could not be explained by current theory,” said MINOS co-spokesperson Jenny Thomas. “While the neutrinos and antineutrinos do behave differently on their journey through the Earth, the Standard Model predicts the effect is immeasurably small in the MINOS experiment. Clearly, more antineutrino running is essential to clarify whether this effect is just due to a statistical fluctuation.”

The MINOS experiment involves more than 140 scientists, engineers, technical specialists and students from 30 institutions, including universities and national laboratories, in five countries: Brazil, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Funding comes from: the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation in the U.S., the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the U.K; the University of Minnesota in the U.S.; the University of Athens in Greece; and Brazil’s Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo (FAPESP) and National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Fermilab is a national laboratory funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

- Scientists know that there exist three types of neutrinos and three types of antineutrinos. Cosmological observations and laboratory-based experiments indicate that the masses of these particles must be extremely small: Each neutrino and antineutrino must weigh less than a millionth of the weight of an electron.

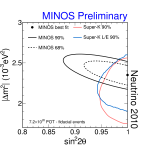

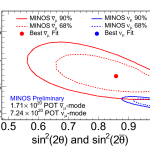

- Neutrino oscillations depend on two parameters: the square of the neutrino mass difference, Δm2, and the mixing angle, sin22θ. MINOS results (shown in black), accumulated since 2005, yield the most precise known value of Δm2, namely Δm2 = 0.0024 ± 0.0001 eV2

- The oscillations of antineutrinos also depend on two parameters: the square of the antineutrino mass difference, Δm2, and the antineutrino mixing angle, sin22θ (shown in red). MINOS has found Δm2 = 0.0034 ± 0.0004 eV2. The MINOS neutrino results are show in blue for comparison. Theorists expected the values for neutrinos and antineutrinos to be the same.

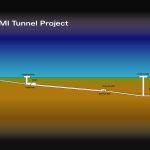

- Neutrinos, ghost-like particles that rarely interact with matter, travel 450 miles straight through the earth from Fermilab to Soudan — no tunnel needed. The Main Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search (MINOS) experiment studies the neutrino beam using two detectors. The MINOS near detector, located at Fermilab, records the composition of the neutrino beam as it leaves the Fermilab site. The MINOS far detector, located in Minnesota, half a mile underground, again analyzes the neutrino beam. This allows scientists to directly study the oscillation of muon neutrinos into electron neutrinos or tau neutrinos under laboratory conditions.

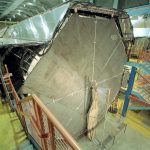

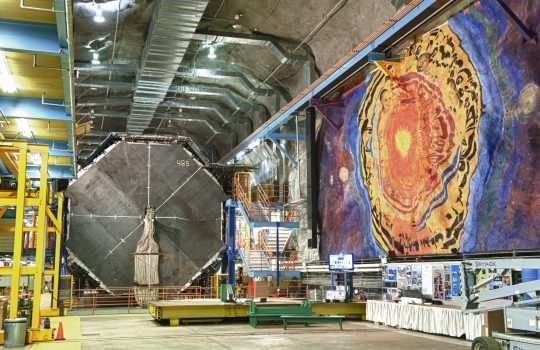

- The MINOS far detector is located in a cavern half a mile underground in the Soudan Underground Laboratory, Minnesota. The 100-foot-long MINOS far detector consists of 486 massive octagonal planes, lined up like the slices of a loaf of bread. Each plane consists of a sheet of steel about 25 feet high and one inch thick, with the last one visible in the photo. The whole detector weighs 6,000 tons. Since March 2005, the far detector has recorded neutrinos from a beam produced at Fermilab. The MINOS collaboration records about 1,000 neutrinos per year.

- The 1,000-ton MINOS near detector sits 350 feet underground at Fermilab. The detector consists of 282 octagonal-shaped detector planes, each weighing more than a pickup truck. Scientists use the near detector to verify the intensity and purity of the muon neutrino beam leaving the Fermilab site. Photo: Peter Ginter

- Fermilab completed the construction and testing of the Neutrino at the Main Injector (NuMI) beam line in early 2005. Protons from Fermilab’s Main Injector accelerator (left) travel 1,000 feet down the beam line, smash into a graphite target and create muon neutrinos. The neutrinos traverse the MINOS near detector, located at the far end of the NuMI complex, and travel straight through the earth to a former iron mine in Soudan, Minnesota, where they cross the MINOS far detector. Some of the neutrinos arrive as electron neutrinos or tau neutrinos.

- When operating at highest intensity, the NuMI beam line transports a package of 35,000 billion protons every two seconds to a graphite target. The target converts the protons into bursts of particles with exotic names such as kaons and pions. Like a beam of light emerging from a flashlight, the particles form a wide cone when leaving the target. A set of two special lenses, called horns (photo), is the key instrument to focus the beam and send it in the right direction. The beam particles decay and produce muon neutrinos, which travel in the same direction. Photo: Peter Ginter

- More than 140 scientists, engineers, technical specialists and students from Brazil, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States are involved in the MINOS experiment. This photo shows some of them posing for a group photo at Fermilab, with the 16-story Wilson Hall and the spiral-shaped MINOS service building in the background.

- Far view The University of Minnesota Foundation commissioned a mural for the MINOS cavern at the Soudan Underground Laboratory, painted onto the rock wall, 59 feet wide by 25 feet high. The mural contains images of scientists such as Enrico Fermi and Wolfgang Pauli, Wilson Hall at Fermilab, George Shultz, a key figure in the history of Minnesota mining, and some surprises. A description of the mural, painted by Minneapolis artist Joe Giannetti, is available here.