Editor’s note: Below is a press release from the University of Chicago announcing an exciting new result from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), an array of radio telescopes located around the world. Included in that array is the South Pole Telescope (SPT), which is operated by a collaboration of more than 80 scientists and engineers from a group of universities and U.S. Department of Energy national laboratories, including three institutions in the Chicago area.

These research organizations — the University of Chicago and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and Argonne National Laboratory — worked together to build an ultrasensitive camera for the telescope, called SPT-3G, which contains 16,000 superconducting detectors. Exploiting the technical capability and expertise of its Silicon Detector Facility, Fermilab led the assembly of the detector modules and their integration into the SPT-3G camera, which was designed by Bradford Benson of Fermilab and the University of Chicago. On EHT, Fermilab scientists helped to design the EHT receiver interface and installation on the SPT and have supported EHT observations through their leading roles on SPT-3G survey and SPT telescope operations. Fermilab’s work on the South Pole Telescope is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

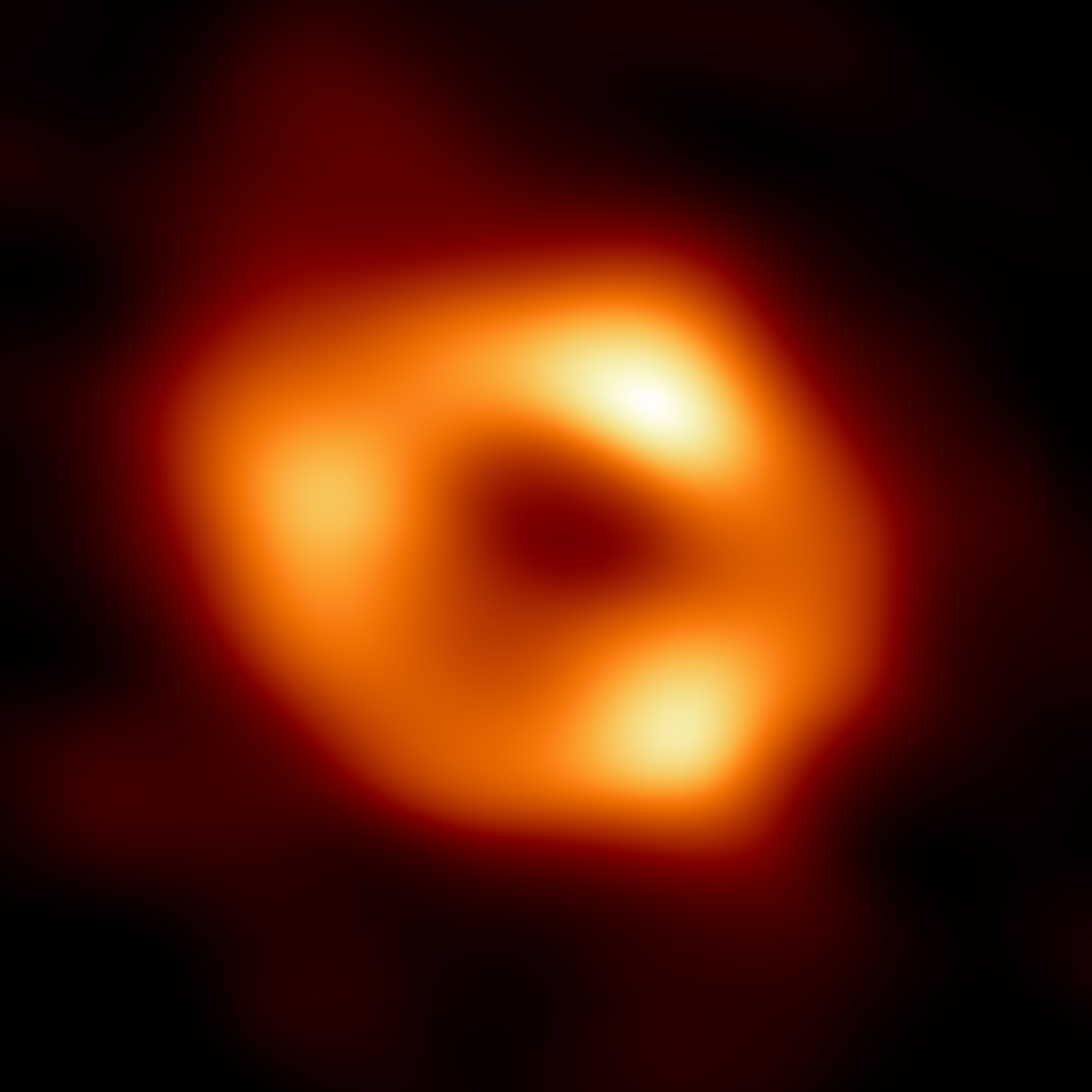

Astronomers have unveiled the first image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy. This result provides overwhelming evidence that the object is indeed a black hole and yields valuable clues about the workings of such giants, which are thought to reside at the center of most galaxies.

The image was produced by a global research team called the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, using observations from a worldwide network of radio telescopes including the University of Chicago-affiliated South Pole Telescope.

First image of the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. This is the first image of Sagittarius A* (or Sgr A* for short), the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. It’s the first direct visual evidence of the presence of this black hole. It was captured by the Event Horizon Telescope, an array which linked together eight existing radio observatories across the planet to form a single “Earth-sized” virtual telescope. The telescope is named after the “event horizon”, the boundary of the black hole beyond which no light can escape. Although we cannot see the event horizon itself, because it cannot emit light, glowing gas orbiting around the black hole reveals a telltale signature: a dark central region (called a “shadow”) surrounded by a bright ring-like structure. The new view captures light bent by the powerful gravity of the black hole, which is four million times more massive than our Sun. The image of the Sgr A* black hole is an average of the different images the EHT Collaboration has extracted from its 2017 observations. Photo: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration

The image is a long-anticipated look at the massive object that sits at the very center of our galaxy. Scientists had previously seen stars orbiting around something invisible, compact, and very massive at the center of the Milky Way. This strongly suggested that this object — known as Sagittarius A* — is a black hole, and today’s image provides the first direct visual evidence of it.

Although we cannot see the black hole itself, because it is completely dark, glowing gas around it reveals a telltale signature: a dark central region (called a “shadow”) surrounded by a bright ring-like structure. The new view captures light bent by the powerful gravity of the black hole, which is four million times more massive than our Sun.

“We were stunned by how well the size of the ring agreed with predictions from Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity,” said Event Horizon Telescope Project Scientist Geoffrey Bower from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei. “These unprecedented observations have greatly improved our understanding of what happens at the very center of our galaxy, and offer new insights on how these giant black holes interact with their surroundings.”

The results are being published today in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Because the black hole is about 27,000 light-years away from Earth, it appears to us to have about the same size in the sky as a donut on the Moon. To image it, the team created the powerful Event Horizon Telescope, which linked together eight existing radio observatories across the planet to form a single “Earth-sized” virtual telescope.

The Event Horizon Telescope observed Sagittarius A* (known for short as Sgr A*, pronounced “sadge-ay-star”) on multiple nights, collecting data for many hours in a row, similar to using a long exposure time on a camera.

One of these telescopes was the South Pole Telescope, operated by an international collaboration led by the University of Chicago and located at NSF’s Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Its unique remote geographic location at the South Pole provides the Event Horizon Telescope its highest-resolution information and a 24-hour-a-day view of the galactic center.

Even though the South Pole Telescope is used primarily for a different scientific goal – it is one of the most sensitive instruments in the world built to measure the light left over from the Big Bang – its crew jumped at the chance to be part of the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration.

“Scientists have been investigating the object at the center of our galaxy since I was a student decades ago, and it is exciting to be part of an experiment that can definitively image the black hole that we know must be there,” said University of Chicago Prof. John Carlstrom, who directs the South Pole Telescope team. “These observations give us an unprecedented view of gravity in one of the most extreme environments in our universe. It’s very cool to have this remarkable image where we can see the shadow of the black hole.”

The breakthrough follows the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration’s 2019 release of the first image of a black hole, called M87*, at the center of the more distant Messier 87 galaxy. The two black holes look remarkably similar, even though our galaxy’s black hole is more than a thousand times smaller and less massive than M87*.

“We have two completely different types of galaxies and two very different black hole masses, but close to the edge of these black holes they look amazingly similar,” said Sera Markoff, co-chair of the Event Horizon Telescope Science Council and a professor of theoretical astrophysics at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. “This tells us that General Relativity governs these objects up close, and any differences we see further away must be due to differences in the material that surrounds the black holes.”

This achievement was considerably more difficult than for M87*, even though Sgr A* is much closer to us.

“The gas in the vicinity of the black holes moves at the same speed — nearly as fast as light — around both Sgr A* and M87*. But where gas takes days to weeks to orbit the larger M87*, in the much smaller Sgr A* it completes an orbit in mere minutes,” Event Horizon Telescope scientist Chi-kwan (‘CK’) Chan, from Steward Observatory and Department of Astronomy and the Data Science Institute of the University of Arizona, explained.

“This means the brightness and pattern of the gas around Sgr A* was changing rapidly as the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration was observing it — a bit like trying to take a clear picture of a puppy quickly chasing its tail.”

The researchers had to develop sophisticated new tools that accounted for the gas movement around Sgr A*. While M87* was an easier, steadier target, with nearly all images looking the same, that was not the case for Sgr A*. The image of the Sgr A* black hole is an average of the different images the team extracted, finally revealing the giant lurking at the center of our galaxy for the first time.

The effort was made possible through the ingenuity of more than 300 researchers from 80 institutes around the world that together make up the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. In addition to developing complex tools to overcome the challenges of imaging Sgr A*, the team worked rigorously for five years, using supercomputers to combine and analyse their data, all while compiling an unprecedented library of simulated black holes to compare with the observations.

Even just getting all the data to the collaboration to analyse was a logistical challenge, especially for the South Pole Telescope. Its remote location gives it an excellent view of SgrA*, but the enormous amount of data it gathers is too large to send by the limited internet available at the South Pole. The data had to be collected on discs and flown out by plane—which can only happen during the Antarctic summer, between November and February, when the weather is safe enough to fly.

Scientists are particularly excited to finally have images of two black holes of very different sizes, which offers the opportunity to understand how they compare and contrast. They have also begun to use the new data to test theories and models of how gas behaves around supermassive black holes. This process is not yet fully understood but is thought to play a key role in shaping the formation and evolution of galaxies.

“Now we can study the differences between these two supermassive black holes to gain valuable new clues about how this important process works,” said Event Horizon Telescope scientist Keiichi Asada from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei. “We have images for two black holes — one at the large end and one at the small end of supermassive black holes in the Universe — so we can go a lot further in testing how gravity behaves in these extreme environments than ever before.”

Progress on the Event Horizon Telescope continues: a major observation campaign in March 2022 included more telescopes than ever before. The ongoing expansion of the Event Horizon Telescope network and significant technological upgrades will allow scientists to share even more impressive images as well as movies of black holes in the near future.

The South Pole Telescope collaboration is led by the University of Chicago and includes research groups at over a dozen institutions, including the UChicago-affiliated Argonne and Fermi national laboratories. Specialized Event Horizon Telescope instrumentation was provided by the University of Arizona. The participation of the South Pole Telescope in the Event Horizon Telescope is funded primarily by the National Science Foundation.