‘Flash photography’ at the LHC

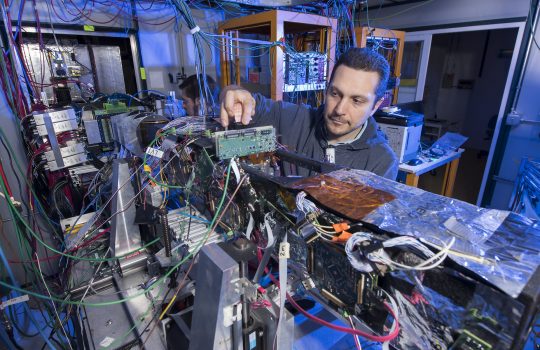

What if you want to capture an image of a process so fast that it looks blurry if the shutter is open for even a billionth of a second? This is the type of challenge scientists on experiments like CMS and ATLAS face as they study particle collisions at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. An extremely fast new detector inside the CMS detector will allow physicists to get a sharper image of particle collisions.