The Mu2e experiment, hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, reached an important milestone in November as the collaboration moved a key component of the experiment, called the tracker, across the Fermilab campus into Mu2e Hall.

“This is a major moment for Mu2e,” said Bob Bernstein, Mu2e co-spokesperson. “Soon, we’re going to be able to start looking at our first particle tracks from cosmic rays passing through all of our detectors.”

Although the Standard Model of particle physics is scientists’ best explanation for how the universe works, it doesn’t account for phenomena like dark matter and dark energy. So, scientists are on the hunt for new physics.

Subatomic particles called muons are in the same family as electrons: charged leptons. The Standard Model dictates that when a muon decays into an electron, two neutrinos are also produced. But physicists believe it’s possible that charged leptons convert directly into each other.

Mu2e, as its name suggests, will be looking for the direct conversion of a muon into an electron without producing neutrinos. From previous experiments, scientists know that this hypothetical muon-to-electron conversion would be extremely rare. If the phenomenon occurs, it will happen less often than once every 1 trillion muon decays.

“And Mu2e is going to produce one muon for every grain of sand on Earth’s beaches, which is kind of an incomprehensible number of muons.”

Brendan Kiburg, Mu2e tracker project manager

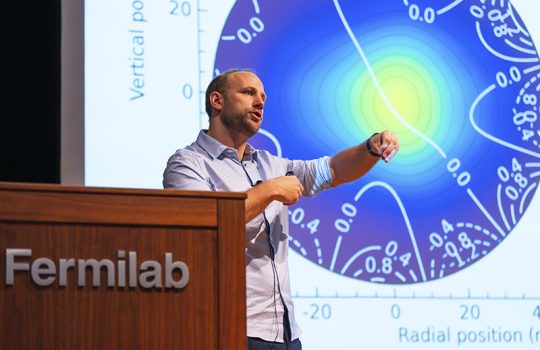

“One of the keys to intensity frontier experiments is designing an experiment that enables us to look at a process very quickly and then repeat that billions, if not trillions of times,” said Brendan Kiburg, a project manager for the Mu2e tracker. “And Mu2e is going to produce one muon for every grain of sand on Earth’s beaches, which is kind of an incomprehensible number of muons.”

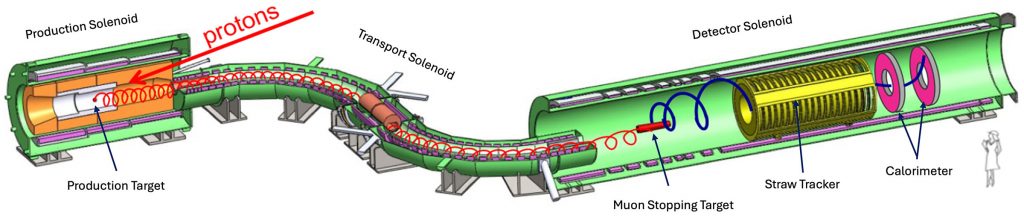

To handle so many muons, Mu2e has a unique, sinuous design. Three magnets make up the body of the experiment. The first magnet is called the production solenoid. This is where the muons are produced. The transport solenoid then delivers those muons into the detector solenoid that will hold Mu2e’s subdetectors. There, the muons encounter an aluminum target where they are stopped, captured and potentially undergo this hypothetical muon-to-electron conversion. The secondary particles produced will then encounter the first subdetector, called the tracker.

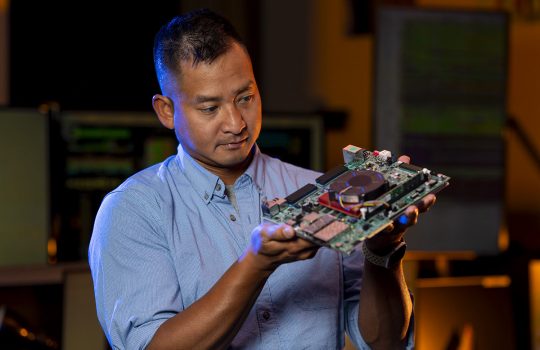

“The Mu2e tracker is an interesting construction because we didn’t want to have any mass on the inside of the tracker to interfere with the particles we’re trying to detect,” said Kiburg.

This design also helps the experiment weed out particles at the wrong energies.

As an electron enters the detector solenoid, the magnetic field will force the particle to spiral. If an electron has too low a momentum, the spiral is too tight, and it will never encounter the tracker, leaving the subdetector without ever interacting. But a higher momentum particle, which is more likely to be within the desired energy range, can spiral into the heart of the detector and produce a signal.

To complement the tracker, another subdetector, called the calorimeter, is installed downstream in the detector solenoid. While the tracker will have the precision to measure the momentum of the signal, the calorimeter will check its energy and timing, allowing the collaboration to definitively identify the particle as an electron. The calorimeter will also be an important step in cleaning up the particle tracks identified by the tracker.

The third subdetector is the cosmic ray veto that surrounds the detector solenoids and, as its name implies, helps identify cosmic ray tracks before they enter the tracker and calorimeter so that they can be easily eliminated.

“Thanks to this sophisticated detection system, we can beautifully reconstruct the candidate particle’s momentum,” said Stefano Miscetti, Mu2e co-spokesperson. “So, if we say this event is just an electron, there will be no doubt that we saw just an electron.”

Now that the tracker has joined the calorimeter and cosmic ray veto at the Mu2e Hall, the experiment can begin integrating the three subdetectors together to be read out by Mu2e’s data acquisition system.

At that point, the experiment will be able to start testing the ensemble of detectors with cosmic rays. This will enable the collaboration to calibrate the signals from the subdetectors before the beam is sent to the detector. “Mu2e is one of the most exciting experiments to start looking for new physics in the muon sector,” said Miscetti. “We have been working on this system for more than 10 years, and now we finally see the experiment taking shape.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.