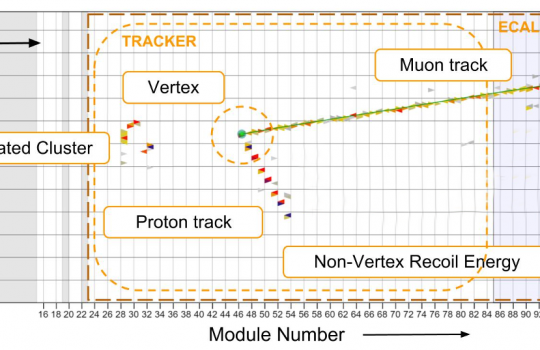

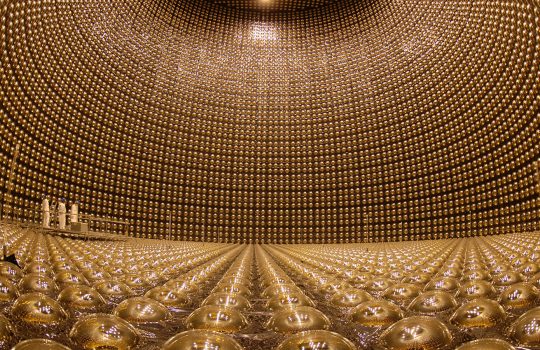

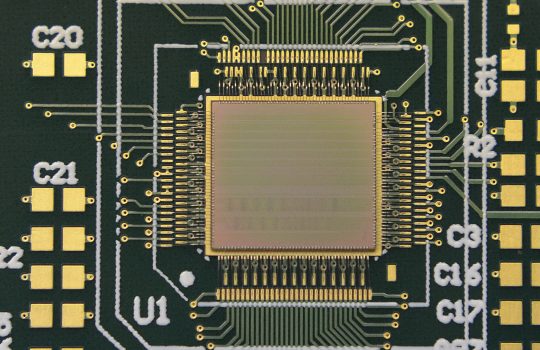

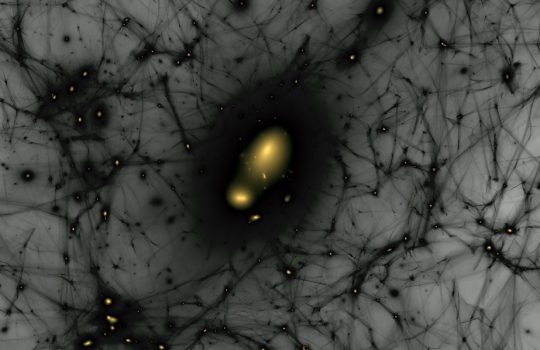

When scientists begin taking data with the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment in the mid-2020s, they’ll be able to peer 13.8 billion years into the past and address one of the biggest unanswered questions in physics: Why is there more matter than antimatter? To do this, they’ll send a beam of neutrinos on an 800-mile journey from Fermilab to Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. To detect neutrinos, researchers at several DOE national laboratories, including Fermilab, are developing integrated electronic circuitry that can operate in DUNE’s detectors — at temperatures around minus 200 degrees Celsius. They plan to submit their designs this summer.