Four outstanding researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory were presented 2025 Universities Research Association Honorary Awards during a ceremony at Fermilab earlier this year. URA is a consortium of over 90 leading research-oriented universities, primarily in the United States, and also in Italy and the United Kingdom.

“This year’s awardees remind us that science thrives when brilliant minds come together with persistence and purpose, laying the groundwork for future generations.”

John Mester, URA President and CEO

“Each of these awards tells a story of discovery, commitment and collaboration,” said John Mester, URA President and CEO. “Celebrating researchers at every career stage honors their extraordinary contributions to Fermilab’s mission and highlights their essential role in advancing U.S. scientific leadership. This year’s awardees remind us that science thrives when brilliant minds come together with persistence and purpose, laying the groundwork for future generations.”

Doctoral Thesis Award — Gray Putnam

The URA Honorary Doctoral Thesis Award was presented to Gray Putnam, a Lederman Science Fellow at Fermilab, whose dissertation described the data taking, processing, calibration and analysis that led to the first complete physics result of the ICARUS experiment at Fermilab.

As part of Fermilab’s Short-Baseline Neutrino program, ICARUS is a liquid-argon time projection chamber, or LArTPC, that detects neutrinos produced by the Fermilab accelerator complex. LArTPCs consist of a tank of liquid argon containing a high-voltage cathode plane across from a set of anode detector planes. Charged particles traveling through the liquid argon ionize argon atoms, liberating electrons, and an electric field applied to the system causes these electrons to drift toward the anode planes.

“We detect those ionization electrons, and that detection forms the actual image,” said Putnam. “They’re wonderfully visual. That’s my favorite thing about working with this technology — you can actually see everything that the particles do, which is rare in particle physics.”

As a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Putnam helped calibrate ICARUS by refining the LArTPC, likening it to correcting lens distortion in a camera. Just as a camera’s lens alters how objects appear, Putnam explained, the way ionization signals are detected in a LArTPC can distort particle tracks.

Initially, there was a mismatch between simulated and real data in ICARUS, leading to an incorrect representation of the detector’s behavior. So, Putnam developed a tuning procedure to address this, and the real data and simulations came back into alignment. With the detector properly calibrated, the entire physics program for ICARUS was enabled.

In the award citation, URA specifically praised Putnam’s “pioneering work to understand and quantify novel effects” in LArTPCs, which will be vital for current and future experiments.

Early Career Award — James Mott

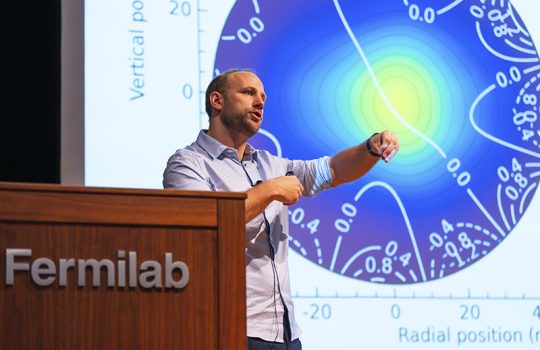

Fermilab scientist James Mott received this year’s URA Honorary Early Career Award “for his leadership and scientific contributions to the Muon g-2 experiment,” one of Fermilab’s most notable particle physics experiments.

Muon g-2 measured the wobble of a subatomic particle called the muon, which is similar to the electron but about 200 times its mass. Theoretical physicists created predictions of its wobble, known as the magnetic moment of the muon, and experimental physicists made measurements to test if the values agreed.

In June, the Muon g-2 collaboration published their third and final measurement of the magnetic moment, which agreed with their previous measurements and surpassed their targeted precision.

Mott began working on Muon g-2 when he became a postdoctoral researcher at Boston University in 2014. At that time, Muon g-2 at Fermilab was ramping up, and Mott was in an ideal place to jump onboard.

Mott ended up leading the design effort for electronics for the experiment’s tracker system. He stayed involved for its prototyping, installation, commissioning and operation. As the tracker installation began in 2016, Mott became based at Fermilab full time.

By the time Muon g-2 started taking data in 2018, Mott had built up vast knowledge in different areas of the experiment. During the first physics data-taking run, Run 1, he participated in the analyses of the data and assisted with corrections to the beam dynamics. “I kind of dipped my toe in quite a lot of different analysis areas,” he said. In 2020, Mott officially joined Fermilab as a Wilson Fellow.

For Runs 2 and 3 of the experiment, Mott was the analysis coordinator. “The second unblinding, for me personally, was really important,” he said. “That was my baby. The relief when that one agreed with our previous result was really powerful.”

That leadership during Runs 2 and 3, as well as his contributions to beam dynamics corrections, earned Mott the URA Honorary Early Career Award.

Today, Mott continues contributing as a reviewer for the collaboration’s next analysis and is transitioning to another muon experiment at Fermilab — Mu2e — ensuring lessons from Muon g-2 are passed along.

Tollestrup Award for Postdoctoral Research — Lauren Yates

Lauren Yates, a newly minted assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame, received the 2025 URA Honorary Tollestrup Award for Postdoctoral Research for her work on the Short-Baseline Near Detector, or SBND.

Yates completed her doctoral research on MicroBooNE, part of the trio of detectors in Fermilab’s Short-Baseline Neutrino Program along with ICARUS and SBND. She said she was happy to participate in MicroBooNE’s data analyses but wanted a chance to help build a detector from the ground up. So when it was time for her postdoctoral research at Fermilab, Yates leapt at the chance to join SBND, bringing lessons learned from MicroBooNE to the commissioning of this new detector.

Like ICARUS, the Short-Baseline Near Detector is a liquid-argon time projection chamber: a tank of liquid argon with a high voltage that causes ionized electrons to drift toward the detection plane. SBND requires 100 kilovolts — the equivalent voltage of approximately 8,000 car batteries.

“The whole detector is inside the cryostat, but you can’t put your high-voltage power supply inside the cryostat,” said Yates.

To get the high voltage from the outside power supply into the detector, physicists needed a piece of equipment called a high-voltage feed-through. Yates said it took several months of testing feed-throughs before they finally found one that worked. The day they got the cathode to 100 kilovolts for the first time is one of Yates’s favorite memories from SBND.

At the same time the feed-throughs were being tested, Yates was coordinating SBND’s commissioning. She compared a detector’s commissioning to turning on a car for the first time — except it’s a brand new, one-of-a-kind car that was assembled from scratch and built with parts fabricated by many teams working separately.

“Watching the car just mosey down the driveway for the first time is very exciting,” said Yates. “We got to watch it go from that to doing 60 on the highway with confidence.”

In all, it took nine months to commission SBND. Yates pointed out they had a relatively large team, with up to 50 people contributing much of their time at the busiest point.

“There’s half a dozen or so different subsystems of the detector. For the detector to really, truly fully work, they all have to be coordinated, and they all independently have to achieve certain milestones,” said Yates. “Then everything has to work together to achieve other milestones.”

For her contributions to SBND’s high-voltage system and her leadership of the SBND detector commissioning, Yates received this year’s Tollestrup Award. “I was stunned in the end at how everyone worked so hard, and things really worked out, even though there were serious challenges,” she said.

Engineering Award — Chris Jensen

Chris Jensen began his long career at Fermilab in January 1990 in the same group he is part of today: the Power Electronics Systems Department within the Accelerator Directorate. His first task at Fermilab was to design a pulse-power system for the Main Injector beamline. With a pulse-power system, energy is accumulated and stored over a long period of time and then delivered in short bursts. One use of pulse power in particle accelerators is to transfer particles from one accelerator to another.

For his first 25 years at Fermilab, Jensen worked on everything pulse-power. He designed systems for the Fermilab’s powerful Tevatron accelerator and the European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser Facility in Germany.

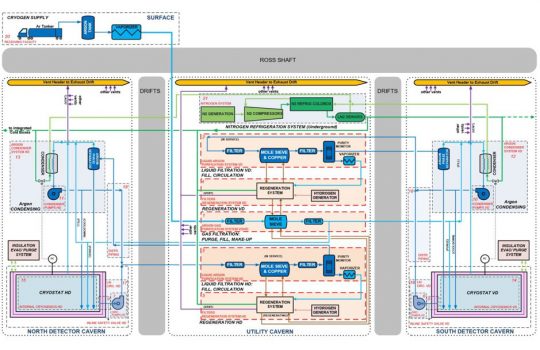

Then, in 2016, Jensen was appointed director of the Power Electronics Systems Department. At the time, his group was working on the horn power supply for the Long Baseline Neutrino Facility, or LBNF. When some colleagues retired, Jensen took over as lead engineer of the project, drawing on his experience from working on the Neutrinos at the Main Injector, or NuMI, and the Booster Neutrino Beam horn power supplies.

The LBNF horn system is a series of pulsed magnetic devices that will focus the beam of secondary particles that make neutrinos. Without the horns, LBNF would generate way fewer neutrinos for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment. So, ensuring the power supply is robust and reliable is necessary for the success of Fermilab’s flagship experiment.

Because the Long Baseline Neutrino Facility horn system is designed to last 30 years, it must be tested thoroughly. Once installed and operational, accessing and repairing the system is neither easy nor practical. And if a faulty power supply caused any of the horns to fail, it would take a long time to replace them. Jensen and his team have been testing the power supply prototype over the last year, identifying and fixing the parts that need attention. They are now in production for a power supply to test individual LBNF horns before they are installed in the final system.

“This is really the culmination of years of work,” said Jensen. “Design started at least 10 years ago, and now it’s finally coming to fruition. The hard part is not the design, it’s making it work.”

Jensen has been in the Power Electronics Systems Department — though the group’s name has evolved over the years — for his entire Fermilab career. Two years ago, he became deputy department head, and he is now looking forward to letting others lead new projects.

This year’s URA Honorary Engineering Award recognizes his “invaluable three-and-a-half-decade career as an expert in power electronics systems, culminating in his recent groundbreaking work proving a prototype power supply for the LBNF Horn Focusing System, a critical achievement for the DUNE experiment.”

“It’s really been a group effort, said Jensen. “I owe a lot of thanks to a lot of people. I received the award, but there have been a whole lot of people contributing.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.